Description

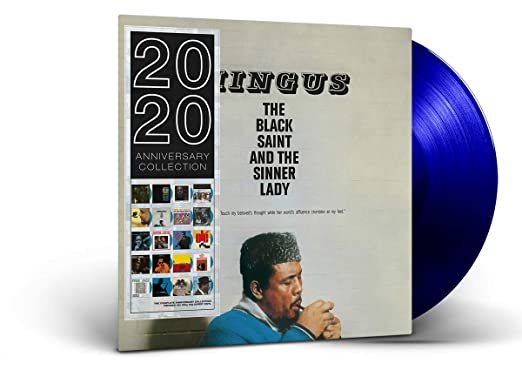

*This is a Vinyl LP*

Release Date: 2013

Label: DOL

180 Gram Colored Vinyl

Track List

Side A

1. Solo Dancer (Stop! And Listen, Sinner Jim Whitney!)

2. Duet Solo Dancers (Heart’s Beat And Shades In Physical Embraces)

3. Group Dancers ([Soul Fusion] Freewoman And Oh This Freedom’s Slave Cries)

Side B

1. Trio And Group Dancers (Stop! Look! And Sing Songs Of Revolutions!)

2. Single Solos And Group Dance (Saint And Sinner Join In Merriment On Battle Front)

3. Group And Solo Dance (Of Love, Pain, And Passioned Revolt, Then Farewell, My Beloved, ’til It’s Freedom Day)

Personnel

Alto Saxophone – Charlie Mariano

Bass, Piano – Charles Mingus

Drums – Dannie Richmond

Guitar – Jay Berliner

Piano – Jaki Byard

Soprano Saxophone, Baritone Saxophone, Flute – Jerome Richardson

Tenor Saxophone, Flute – Dick Hafer

Trombone – Quentin Jackson

Trumpet – Richard Williams, Rolf Ericson

Tuba – Don Butterfield

Review

The Black Saint and the Sinner Lady is one of the greatest achievements in orchestration by any composer in jazz history. Charles Mingus consciously designed the six-part ballet as his magnum opus, and — implied in his famous inclusion of liner notes by his psychologist — it’s as much an examination of his own tortured psyche as it is a conceptual piece about love and struggle. It veers between so many emotions that it defies easy encapsulation; for that matter, it can be difficult just to assimilate in the first place. Yet the work soon reveals itself as a masterpiece of rich, multi-layered texture and swirling tonal colors, manipulated with a painter’s attention to detail. There are a few stylistic reference points — Ellington, the contemporary avant-garde, several flamenco guitar breaks — but the totality is quite unlike what came before it. Mingus relies heavily on the timbral contrasts between expressively vocal-like muted brass, a rumbling mass of low voices (including tuba and baritone sax), and achingly lyrical upper woodwinds, highlighted by altoist Charlie Mariano. Within that framework, Mingus plays shifting rhythms, moaning dissonances, and multiple lines off one another in the most complex, interlaced fashion he’d ever attempted. Mingus was sometimes pigeonholed as a firebrand, but the personal exorcism of Black Saint deserves the reputation — one needn’t be able to follow the story line to hear the suffering, mourning, frustration, and caged fury pouring out of the music. The 11-piece group rehearsed the original score during a Village Vanguard engagement, where Mingus allowed the players to mold the music further; in the studio, however, his exacting perfectionism made The Black Saint and the Sinner Lady the first jazz album to rely on overdubbing technology. The result is one of the high-water marks for avant-garde jazz in the ’60s and arguably Mingus’ most brilliant moment. Steve Huey